The X-Files: I Want To Believe

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Case Profile Six years later, Scully works in a Catholic hospital and Mulder is a hermit in their remote home in rural Virginia. They are pulled back in an FBI investigation involving a pedophile priest pretending to have visions that may help solve a case of abducted women. The abductions prove to be the work of a man trying to save his dying lover thanks to full-body transplants operated by a Russian doctor. This experience strains Mulder and Scully’s relationship but they stand united against a darkness that keeps finding them.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Field Report

Following the series finale, Carter & Spotnitz remained the creative team of the X-Files franchise. “IWTB” was written by Carter & Spontitz, who now seem to act as entirely equal accomplices in the franchise, and directed by Carter, his first feature film directorial debut. To ensure continuity, but also because Carter likes to surround himself with collaborators he trusts, Carter got many key persons of the TenThirteen TV crew behind the scenes for IWTB: cinematographer Bill Roe (and his predecessor John Bartley, here in the second unit), production designer Mark Freeborn, producer Paul Rabwin, visual effects gurus Mat Beck and David Gauthier, and of course assistant director Tom Braidwood and composer Mark Snow (with music editor Jeff Charbonneau)… this list is far from complete! Also, in an explicit will to return to the roots of the show and strike that fine mysterious atmospheric mood that made it successful — and in an implicit confession that the show had strayed from its initial style in its later seasons — the shooting was done in Vancouver.

The X-File Franz Tomczeszyn, of Russian descent, was an altar boy in the Catholic church when he was young; he was one of 36 altar boys to be raped by pedophile priest Joseph Crissman; sadly, XF is once again inspired by true stories. Franz eventually fell in love with Russian emigrant Janke Dacyshyn (they still spoke English between them) and they got married in Massachussets, a State that allows same-sex marriage. Like ‘Krycek’, the names are not Russian (they originate from Spotnitz and Carter’s entourage). But Franz fell ill of lung cancer. To save him, Janke called help from his home country and brought Dr. Uroff-Koltoff and his medical team to the USA. Extreme experiments on dogs in organ transplants and stem cell research had allowed this “Frankenstein“-like doctor to reach an unprecedented rate of success in transplants of entire limbs and even heads, resulting in creatures like a two-headed dog; such transplants were not rejected for weeks. Janke hoped to do the same for Franz, to give him a healthy body. Janke enlisted as an organ transporter in order to gain access to organs and to medical information over organ donors. Organs were stolen and donors were abducted to experiment on human limbs transplants and to perfect the head transplant procedure before attempting it on Franz; the waste organs and bodies were disposed of in the wild, encased in a solidified gelatinous material (“dirty glass“). Whether it was because Janke liked women’s bodies as well (the pool scene) or because his own body reminded him of his experience with Father Joe, Franz asked to have his new body to be that of a woman. Organ donor and FBI Agent Monica Bannon was the first victim whose body received Franz’s head, a decision perhaps precipitated by Franz’s wounding by Bannon. Cheryl Cunningham was then abducted to replace the soon-to-be-rejected body in this yet experimental procedure. In true X-Files fashion, this is arguably directly based on reality: similar experiments were conducted on dogs in the Soviet Union of the 1950s, in the era of extreme medical experiments such as those of Unit 731 (3X10: 731) and the beginnings of eugenics (1X10: Eve) — unless such footage spread in the internet is another hoax perpetrating a modern legend.

Excommunicated from the Church, Father Joe went on to castrate himself to stop his urges and sought for redemption from the Church but more importantly from God himself. He volunteered to live in a dorm for sex offenders, where the offenders “police themselves“; this claustrophobic and grim setting where those rejected by societal norms are thrown into does have something to say about alienation in modern societies — not by advocating paedophilia as something that is acceptable but by pointing out the lack of willingness to believe in the abilities of the individual to change and surpass his mistakes, despite western societies defending the very Catholic concept of forgiveness. (Ex-)Father Joe came by his own volition to the FBI claiming to have visions of these abductions, visions similar to what we saw in 3X08: Oubliette or 5X16: Mind’s Eye. The fact that we do not ‘see’ Father Joe’s visions adds to the doubts over the veracity of his claims. In many X-Files episodes, and initially in the premise of the show itself, no definitive answers were given, giving both the rational and the paranormal explanations valid arguments but not giving definitive closure at the end. When he says that Bannon is alive just when her severed head was found, a part of her is in fact alive: the part of her attached to Franz — so proof that he was a fraud could also be interpreted as proof that his visions are true. Joe and Franz suffer seizures simultaneously, their eyes bleed blood and they suffer and die from lung cancer at the same moment.

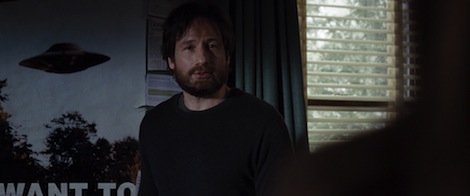

The Joe-Franz connection and Joe’s visions are ultimately unarguably real, but the unknown factor is the why: why did Joe started having these visions and who sent them to him? Joe’s visions come randomly, he does not command them just as he did not command his paedophiliac impulses. Quotes of holy scripture find their way into the dialogue: “through dirty glass” comes from Corinthians 13:12 (“For now we see in a mirror dimly”, more known as “through a glass darkly”) and Father Joe’s “Proverbs 25:2” supernaturally helps Scully to locate the villains in the end. Further shades of grey can be added by noting that the murderous deeds Franz is capable of in the present can be traced back to the scars left by Joe’s own deeds on a younger Franz — evil begetting evil as an aspect of human nature. The moral ambiguity and complex narrative of the involvement of God with a pedophile priest leading or being led to stop a strain of murders, the creation of which he himself contributed, is the heart of IWTB‘s X-File. Thus the story of IWTB mixes two very X-Filish subjects in a convulted story — extreme science with supernatural visions — and indeed fulfils its promise of returning to the roots of the show, with reminiscence of episodes like 1X15: Young at Heart or 3X04: Clyde Bruckman’s Final Repose. Mulder and Scully steal the show As Spotnitz stresses, IWTB‘s real focus is the Mulder and Scully relationship, done to an extent that the formulaic nature of the TV series, balanced between casework and mytharc imperatives, was unable to provide for. This is a very personal story, a human drama that indeed was never attempted in the series — and despite my little fondness for the ‘MSR’ it is reassuring to see these two tortured souls grow together. Perhaps the biggest gamble IWTB took was to present two bleak, mature characters as its leads, also reinforced by the winter setting. After The Truth, Mulder and Scully retreated into semi-anonymity in a house in rural Virginia, where they lived as a couple away from the FBI and its growing infiltration by the alien Supersoldiers. Six years later, they are still themselves. Mulder is still somewhat of a hermit, grew a beard, recreated his office in his home, full of case files and newspaper clippings. Scully is still a scientist; she realized her dream of becoming a doctor by joining in a catholic hospital, keeping with her religious faith.

The ex-agents are drawn back in casework. The previously familiar halls of the FBI headquarters now feel menacing to the two leads, halls now filled with agents looking at them as aliens whodo not belong there, a situation made even more weird by the presence of President Bush’s portrait — apart from the tragic/comedic unexplainable nature of his presence there, the X-Files were also absent for 6 of the 8 years of his term. Mulder accepts to join the investigation only if Scully comes along: “I’m only part of the team“, Mulder says. Mulder is the one the FBI asks for, but he is ineffective alone; when Mulder storms the Russians’ lair in the end, like a lonesome cowboy waving his gun, he is destined to fail. As we know, they can work and ‘fight the future’ only together. Once Mulder gets involved, he is consumed by his work. The reference to his sister Samantha is not fortuitous nor does it invalidate its earlier resolution: Samantha is the ultimate and timeless symbol for Mulder’s Quest, the scar that he will always be reminded of and will always set him out to another search. For him, re-establishing the Truth, in this case about the sincerity of the disgraced Father Joe’s claims, is important for its own sake, even if the man this is all about is no longer of this world.

IWTB‘s extra focus on Scully, both in her dedicated storyline in the hospital and in her being the one that comes to the rescue of her partner, somehow counterbalances Fight the Future‘s focus on Mulder. Scully thought she would be able to syncretize harmoniously her two inclinations, faith and science, in a catholic hospital, however she comes against thorns there as well. She starts acting alone and outside what the mainstream thinking of the clergy and hospital administration allows. By the film’s end, where she is observed and looked down at by three nuns as she is about to perform the operation, she has ‘successfully’ become an outsider to that organization just like Mulder had been named “Spooky Mulder” from within the FBI so many years before. Still, it is not science nor religious faith that Scully rejects: on the contrary, she believes her devotion to medicine and her christian faith to be pure. What IWTB criticizes is organized religion and conventions in the practice of science. A rejection of institutions has been a trademark of the X-Files and indeed all of Carter’s works: the military and the government in the X-Files (“a collaboration of men” as Mulder says in The Truth), the alieating and faceless society in “Millennium“, the Church in IWTB. All in all, many aspects of IWTB remind of “Millennium” (or, to be more precise, its first season, which was exclusively Carter’s creation) more than “The X-Files“: more adult characters, a more realistic approach, an evil originating from Man rather than monsters or aliens, some religious overtones, Bible quotes involved in the storyline. There are even explicit references: the scene of a ‘psychic’ character leading an investigative task force to bodies hidden underground is found both in IWTB and in the pilot of Millennium (with Frank Black in the role of Father Joe)! The trouble with the script So with all these fine and interesting elements, why does the outcome feel like less than the sum of its parts? If a moderate noromo tells you that the best scenes of the film were those involving Mulder and Scully, you know there’s something wrong! IWTB‘s principal character intrigue is a debate between Mulder and Scully over their trademark character traits: Mulder’s readiness to believe and complete devotion to a case, and Scully’s desire for a life free of all that (“darkness“). Given their situation as a couple, however, IWTB ends up being nothing more than a couple’s mundane argument over non-mundane things. Considering the profound roots of their relation, the intrigue does not come across as very engaging or perilous for their future together. Scully’s instantaneous change of opinion over what they should do (first she pulls Mulder into the case, then she wants him out) further harms suspension of disbelief. The script was (re-)written to focus more on the Mulder/Scully relationship and this in concept could have made a fine movie, but this displaced the “monster of the week” aspect by too much. Ambitions of making “XF2” a character study are noble, but XF has always been about the plot rather than the characters, even in its more character-driven episodes (the mythology), and despite its good starting ideas a strong plot is what IWTB lacks. All the layers and moral depth spawning from the case as described above are not encouraged by the plot but are rather results of a research from viewers to connect the dots; when once this could have been considered as clever and intelligent storytelling, here it feels forced and artificial. The stairway discussion in 4X24: Gethsemane is strikingly more powerful and more to the point than anything IWTB has to say on faith.

The X-Files were famous for developing memorable villains. IWTB‘s villains are very sketchily fleshed out and they are hardly given any scenes to develop: apart from scenes that exist for thrills and merely establish them as antagonists with dark motivations and the short finale, they are given no scene to shine in, no spooky lines or confessions that would make memorable actor moments. The main villain is just that, a menacing villain; and I don’t care if he’s a cliché Russian ambisexual pervert, his Russian ambisexual pervert partner must definitely think he needs a toothbrush! The storyline presented Franz and Janke, whose actions are only the reflection of how far they are willing to go to keep their love alive: the murders are only the side-effect of a labour of love (a story very similar to that of horror B-movie “The Brain that wouldn’t Die” (1962)). But if the Russian couple is the anti-Mulder and Scully, in that they go to unethical extremes in the name of love, this was lost in the transition from story to script: we are given far too little to connect with them and feel for them. The X-Files also excelled in its supporting characters. Father Joe’s ‘bleeding eyes’ made for a beautiful shock factor shot and went no further than that, but his argument with Scully was a great moment for Connolly and Anderson. In the end Father Joe’s complex and toned down character makes a decent addition to XF’s long list of psychics such as Luther Lee Boggs (1X12: Beyond the Sea) or Clyde Bruckman (3X04: Clyde Bruckman’s Final Repose). The other supporting characters are strikingly stereotyped and underused. Whitney and Drummy are like younger versions of Mulder and Scully, one a believer in the fringes of the FBI and one agent that gives those theories little credit. Whitney’s character was becoming interesting with her potentially coming between Mulder and Scully (if that soap operatic element can be called interesting), but this storyline was cut short when she was killed off too prematurely, to establish the villain as a real threat. Just then, when Drummy could have become more important, he is offed in order to accomodate a cameo by Skinner. Either character, Drummy or Skinner, could have filled both roles and the character would have gained in depth, but as it is Drummy’s insignificance is accentuated.

A series of storytelling shortcuts and simplifications further detracts from the film. Scully convinces Christian’s parents to continue his treatment with a simple ‘what if’. Scully uses Google (not even GoogleScholar!) and websites that look straight out of 1990s Geocities to learn on Stem Cell Research and becomes a specialist in a demanding medical topic overnight. Mulder’s humor is like that of old, right until it becomes repetitive (there are nine “ass” jokes in a row). Scully’s “scratchy beard” and “just a little something?” lines feel ripped off a bad fanfic and are violently out of character. The opportunity of having an “XF2” is used to pepper the film with a load of private jokes, a technique already used in the opening credits of season 9; as cute and appreciated as they may be, they serve no real purpose and do not make up for storytelling shortcomings. The biggest shortcoming may be that the case is solved by both Mulder and Scully independently and simultaneously, and thanks to coincidences on both their behalf. Mulder’s investigative skills lead him to the villain thanks to a simple visit to a local store; stem cell research for organ transplants and for curing Christian allow the two storylines to cross, but Scully having a revelation by finding the villain’s research on the internet through a non-related search draws the odds extremely. There is little actual investigation and the case is wrapped up too quickly. All those are little things — but they pile up to too much. Finally, it is proof of the script’s imperfection that unintended conclusions are drawn from it. And I’m not only talking about accusations of homophobia that barely stand. “Don’t give up” may be a nice, if simplistic, motto, however the decision to inflict pain on Christian for the sake of the advancement of science when his own parents and the anti-euthanasia Church is willing to let him go does lead to a heavy moral ambiguity. IWTB‘s X-File might have been much stronger in the earlier lost draft, but many subtelties and the elements that made a strong stand-alone story must have been lost somewhere between the rewrite, the shift of focus to Mulder and Scully and the way it was executed onscreen. Cinematographical elements The story is not everything: success greatly depends on the story’s treatment by the other cinematic tools.

For IWTB, Carter chose a winter rural setting where everything — landscape and sins — is covered by a pure white snow; the sun never appears (but for the last scene). The Russians’ lair is filled with the sound of menacing dogs and an unhealthy dirt, contradicting with the need for a sterile medical environment. Scalpels are mixed with badly ground axes; the third act is highly evocative of the unsettling mood of golden age horror films. The direction of photography is indeed impeccable. The editing, given the raw material, is fine as well. Notably the two scenes cross-cutting between settings, the teaser and the Janke chase scene, are mastered well: continuity elements serve as transitions (in the teaser: dogs and people falling down and to their knees) and both settings build to a climax (in the chase: the discovery of Bannon’s head and the death of Whitney). Mark Snow’s music is excellent. There is a very modern electronic sound mixed with sampled orchestral passages that we had not heard in the series, along with some occasional touches taken right off the series’ soundscapes. The tune from the Fight the Future score (“Crossroads“) is reprised in “Trip to DC“, finally doing it justice as it was not actually used in the first film. To the trademark XF ambient tracks are added uncharacteristic melodic tracks for the relationship storyline; these are a definite musical success, even though they do not blend as well with the picture — a nostalgic piano sounds too conventional and easy for a kiss scene. Another novelty of the soundtrack is the use of themes, something that XF very rarely used: a chase theme, a love theme and maybe the ‘unremarkable house’ theme.

There are pacing problems with IWTB. Paradoxically, at 105 minutes, the story feels rushed and the movie feels too long. Perhaps by trying too hard to dictate a desolate mood for its matured characters, the flow of the story suffers from sudden shifts between a series of calm scenes and few action pieces. The first third of the film flows well with the joy of reuniting with these charaters. The middle of the film tries to set a tone but dialogue that could use a rewriting in scenes following each other too mechanically give more of an impression that this story was stretched to fill in theatrical shoes. Then the chase scene in the building under construction lasts twice as much as it should and Whitney shouts “Mulder!” about ten times too many. The third act ends with a resolution that is wrapped up too quickly compared to the length of the buildup: Scully knocks down the bad guy and three shots later Scully prepares to undo a complicated medical operation, cut to the next scene. The directing itself, though it fills its role of telling a story, lacks imagination. Only once, the second abduction scene after the pool, is the majestic mountainous landscape rendered in beautiful panoramic shots. There are some good finds, such as the oppressing shots from the point of view of the girl enclosed in the cage, but the rest of the film is painfully linear and seems made for television instead of using the larger angles cinema would benefit from. Carter had excelled in the episodes he directed for the series (2X05: Duane Barry); in his first theatrical direction he seems overly cautious. Meta elements In limbo since the waning ratings of the later seasons, “XF2” was given a shot by Fox in late 2007 only because of the Writers Guild of America strike, which had resulted in Fox not having any major release in the summer of 2008. IWTB was given a go because Carter promised a very fast production and a good return on investment. The script was written and finalized in a matter of weeks — one could say rushed. 6-7 months to have a film ready is amazingly fast. The defenders of IWTB will endlessly complain about the budget (but look at what a feast Darren Aronofsky did with $35 million: “The Fountain” (2006)), the fact that it’s low-key ‘intellectual’ and not blockbuster-like (so is “There Will Be Blood” (2007), $25 million, and countless other generally agreed upon masterpieces), the lousy promotion (but look at what good word of mouth can do with a movie few believed in in the beginning: “The Matrix” (1999), $65 million), the unforseen success of “The Dark Knight” as competition (hardly an argument) or trends in selfish cinema critics (as if a bad reception is the sole result of a conspiracy). However what will remain in history is not the whys and hows but the what: the final product itself. And the truth is that if IWTB featured characters other than Mulder and Scully, this would be a not very memorable movie. Those who were drawn to XF after watching IWTB must be a meager audience share. As Carter says, this was made as a gift to the fans; “XF2” was designed as the last outing of the franchise. The last we see of Mulder and Scully, that much talked about boat scene, is clearly done as a farewell to the fans (or should one say to the shippers, given the word play with ‘ship’); but as much as this was done in a semi-canon fashion and should be taken lightly, seeing these characters in that setting in the X-Files is a very disturbing concept.

During its promotion, Carter stated that XF was all about faith and the search for God. Even if that description applies to only part of the series and what seem to be Carter’s own preoccupations as of 2008, it is irritating to see once again the purpose and message of this body of work re-written and redefined retroactively by its own creator. It had happened again with the purpose of the mytharc (an allegory for post-World War II American fears, now a background to Mulder & Scully’s personal stories), it had happened again with Mulder-Scully relationship (a taboo in the early seasons, now the initial goal of the show). Incidentally, such profound changes put in question the integrity of XF’s creators compared to much more bold statements by the creators of, for example, “The Wire” (2002-2008). There is no doubt that “XF2” was made for the fans that were most vocal since the show ended, meaning shippers; as explained above I would not mind, if the other elements of the film received a similar quality treatment — and I would not mind if this was not endlessly repeated by Carter and especially Spotnitz as the only prism through which the X-Files can be seen. This official stamping redeems the audience share that agrees but at the cost of alienating the share that doesn’t; more about this being for or against change, it is the reductive vision of making it ‘all about’ one thing rather than expressing various ideas in a single canvas that strikes me as a strategic mistake. The door was left open for one last visit to the XF universe, an “XF3” that would wrap up the 2012 colonization mytharc. After a poor Box Office performance, Fox counts on the cult qualities of a franchise like the X-Files, that has a great sleeper hit potential with DVD sales, in order to greelight “XF3”. In more ways than we may know, the ground was prepared for “XF3” in IWTB: casting 1013 alumni Sarah-Jane Redmond in the quasi-silent role of ‘Agent Fossa’, the FBI agent Whitney and Drummy answer to, surely makes her somehow significant to what will follow (is she a Supersoldier?). IWTB‘s obviously rushed script is quite pradoxical given the 6 years that were at the writers’ disposal. It is sad to realize that this writing team could produce higher quality scripts in a shorter time and under much more stress, back when the show was on the air — and this proof in the past is the only thing that still gives hope to “XF3”.

Verdict Carter & Spotnitz argue that they not only did this “XF2” out of nostalgia for XF, but because they had something to say though it. If with IWTB the public feels that something significant is being said about the loss of focus and the coldness of modern societies, imagine what the same people would say if they were to discover “Millennium“, a work far more complete and deep in that aspect! The truth is that the defects and approximations IWTB presents would be quickly forgotten if this had been an episode of the series sandwiched between two better quality episodes — and after all, Fight the Future as well made similar not fully thought out shortcuts in its narrative. But six years’ expectations, and rightfully so for a theatrical feature film, would be satisfied by nothing less than one of the best stand-alones. In the end, this is nothing more than a run-of-the-mill stand-alone episode bettered by Mulder and Scully’s personal stories. Trapped between a more indie approach in the writing of its lead characters and a much more conventional treatment in its production, IWTB is a chimera that only satisfies the immediate needs of the most nostalgic fans. With a number of successful points but with undeniable shortcomings, this “XF2” still asks from its makers to prove that they can reach the heights achieved by the first five seasons of the show and, like previous attempts to re-launch the franchise, falls short of what preceded.

Surveillance Recodings

Father Joe: “It’s here!” Mulder: “I can feel you thinking.” Father Joe: “So you believe in this kind of things?” Scully: “What are you doing?” Agent Drummy: “I don’t believe this.” Scully: “This isn’t my life anymore, Mulder. I’m done chasing monsters in the dark.” Scully: “I don’t think you’re–“ Mulder: “And then we’ll get out of here, just me and you.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

E.T.C 2004-2008

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||