May-12-2013

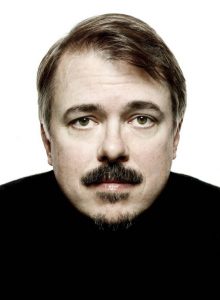

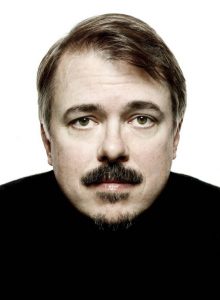

In Conversation: Vince Gilligan on the End of Breaking Bad

Vulture

Jennifer Vineyard

[Original here]

Knee-deep in edits for the final season of Breaking Bad, which premieres in August, the creator of television’s darkest drama talks with Lane Brown about violence as entertainment, the incredible pressure of bringing a beloved serial to an end, and what it feels like to have Dzhokar Tsarnaev as a fan.

How close to the finish line are you?

We’re very close—the shooting was finished April 3, and yesterday we finished editing our second episode of the final eight.

Are you happy?

I feel very happy. There was a great passage of time in the writers’ room where we were a little nervous about the outcome. Well, I shouldn’t speak for them: I was nervous.

In interviews last summer you still weren’t sure how Breaking Bad was going to end. Was this just a matter of specifics? Or had you still not decided whether Walt was going to live, die, or go to prison?

It was everything. We knew very little as of last summer. We knew we had an M60 machine gun in Walt’s trunk that we needed to pay off, and that was about it. We kept asking ourselves, “What would satisfy us? A happy ending? A sad ending? Or somewhere in between?”

You also seemed worried about ending the show badly. If you did end it badly, how would you know?

There are two ways of knowing if something ends badly: If you’re honest with yourself, you just kind of know it. And then there’s other people’s reaction to it. Right now, I am very proud of the final eight episodes. But we could put them on the air in a few months and people could say, “Oh my God. That was the worst ending of a TV series ever.” So then you’re left with that horrible incongruity for the rest of your life. You either think everyone was right, or you start to think, “I’m like the Omega Man. I’m the only one who sees it the correct way and everybody else missed the point.”

Is there too much pressure on a series finale now? Since TV dramas became more serialized and less episodic, and especially since Lost and The Sopranos disappointed everybody, the last few minutes of a show can completely change the way we think about the 60 hours that came first. By contrast, I loved The X-Files, the last big show you wrote for, but I can barely remember how it ended.

There was certainly a lot of self-applied pressure. I second-guessed myself. I was much more neurotic than I usually am, and that’s saying a lot. And there is a different pressure on ending a serialized show versus a non-serialized show. The X-Files is a good example in that it was mostly comprised of stand-alone episodes. But when a show feels like more of a character study, there’s more of an expectation that it will end in a correct and satisfying manner.

And viewers are more sophisticated than ever about storytelling now. TV recappers have made a sport of poking holes in plot work—you have to lay the groundwork for every twist or they’ll hang you. If you were ending Breaking Bad fifteen years ago, you probably could have gotten away with telling us that Walt and Hank had been the same person all along.

Oh, no. At this point, you can parenthetically insert “Gilligan goes pale.”

It helps that I’m not reading what folks are saying online. If I did, there’d be a lot of stuff I’d roll my eyes at, and stuff where I’d say, “Oh shit, we should’ve thought of that.” But the best thing to do, as a showrunner, is to please yourself. It could mean coming up with something that no one will guess. It could mean coming up with the obvious yet satisfying moment. I’m not saying what you’re going to get, but it’s probably going to be a mix of the two. There are things in these last eight episodes that are going to surprise people. There are also things where people will say, “I kind of saw that coming.” But maybe the obvious choice is the right one sometimes.

With shows about difficult-to-like anti-heroes like Walter White, Tony Soprano, or Don Draper, the ending feels extra-important. The finale is when you, the showrunner, render a final verdict on the character and tell us whether your show is in a moral universe where bad people get punished. So, how vengeful a god are you?

I hope that if I were a god, I wouldn’t be a particularly vengeful one. I’ve realized that judging the character is not a particularly fruitful endeavor on my part, and yet I have done that. I’ve lost sympathy for Walter White, personally. Not thinking, I’ve said to Bryan Cranston things like “Walt is such a bastard. He’s such a shit.” Then I realized this might color his perception of the man he’s playing, so I found myself biting my tongue the last six months or so. And my perceptions of Walt have changed in these final eight episodes—I didn’t think that was going to happen.

But this is not a show about evil for evil’s sake. Walt has behaved at times in what could be regarded as an evil fashion, but I don’t think he’s an evil man. He is an extremely self-deluded man. We always say in the writers’ room, if Walter White has a true superpower, it’s not his knowledge of chemistry or his intellect, it’s his ability to lie to himself. He is the world’s greatest liar. He could lie to the pope. He could lie to Mother Teresa. He certainly could lie to his family, and he can lie to himself, and he can make these lies stick. He can make himself believe, in the face of all contrary evidence, that he is still a good man. It really does feel to us like a natural progression down this road to hell, which was originally paved with good intentions.

Why do you think audiences are so enamored of bad guys right now? It’s not just on TV—superheroes are being rewritten as dark, flawed characters.

Our viewing tastes are cyclical. Five years from now, a person like yourself might be asking, “You remember when everybody used to like antiheroes? Now they like the guy in the white hat again. How did that happen? What’s changed in America?” People want what they want, for as long as they want it, then tastes change and something else works. For many decades—and this was reinforced by the broadcast networks’ standards-and-practices department—bad guys on TV had to get their comeuppance, and good guys had to be brave and true and unconflicted. Those were the laws of the business. But people’s tastes are fickle, and now that producers of TV shows can be more nuanced than that, audiences are along for the ride.

Are there any honest-to-God nice characters on TV that you still find interesting?

SpongeBob SquarePants is a great show, and it centers on a character that is courageously nice. Why is SpongeBob interesting? It’s because he has passion. He has a passion for chasing jellyfish. I’m very glad people love Breaking Bad, but the harder character to write is the good character that’s as interesting and as engaging as the bad guy. My hat is off to the SpongeBob showrunners. It’s like how Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did, except backward and in high heels. That’s kind of the struggle you face when you’re writing the good guy now instead of a bad guy.

Bryan Cranston and Gilligan on set in 2011.

Your original pitch for Breaking Bad was that you were going to turn Mr. Chips into Scarface over five seasons. Have you ever felt trapped by that promise?

No. It’s one of the most inadvertently smart things I’ve ever done. I’m not typically that forward-thinking. But the thing that intrigued me about Breaking Bad from day one was the idea of taking a character and transforming him. TV is designed to keep characters in place for years on end. The best example is M*A*S*H: You have a three-year police action in Korea, and they stretched that out to eleven seasons. It was a great show, but when you think about it, a weird unreality overtakes a television series. You see the actors age, and yet the characters don’t. I thought, Wouldn’t it be interesting to do a show in which the character became a slightly different character? We’ve abided by that for five seasons, and I’ve never felt the slightest bit hemmed in. I think that viewers knowing in advance that they were going to get a free-form character that was always in the process of metamorphosis allowed them to be free-form in their expectations.

In this post-Lost world, it seems like the worst sin a TV showrunner can commit is not knowing where his or her show is headed. Telling us there was a basic blueprint probably made it possible for you to say that you didn’t know exactly how the show would end and not get pilloried for it on the Internet. It’s a little like how Game of Thrones can kill its main character in the first season and not make fans think the show’s gone off the rails, because there’s the road map of the book series.

The Walking Dead is another good example—there’s source material for it. The question arises every week: Are they going to stick with what I know, or are they going take another path? So there are those dueling pleasures of “I can’t wait to see something I’ve already read visualized” and “It’s going in a different direction.”

Based on what you know about AMC, do you think it would ever let Rick Grimes lose his hands on The Walking Dead, like he does in the comics?

Does that happen? I’m not up to speed. You ruined it for me!

Sorry.

There are certain realities to making a TV show, and there are the actor’s feelings to consider. If I were the star of a TV show and they came to me and said, “Hey, the comic-book version of this is that you lose your hands,” I’d be like, “Screw that. I need them to act, man. What am I going to do, wear green gloves and you’re going to erase them for the rest of the time I’m on this thing?” It sounds like a big pain in the ass.

You’re in a small club: creators of serialized TV dramas who have elevated the form to art and sustained themselves for five or six seasons—Matthew Weiner, David Chase, David Simon. What do you have in common with those guys?

I know Matt Weiner a fair bit, but I’ve never met David Chase. I guess the short answer is that we all know what we want and we strive hard to get it. I’ve always had a fairly clear picture of who Walter White was, and I’ve got to imagine Matt Weiner knows Don Draper inside and out, as if he’s looking through Don’s eyes.

The other guys all have reputations for being grouchy and difficult. You seem like a nice guy.

I’m putting it on for this interview. I’m pretty dark, as you can guess from watching Breaking Bad. I’ve had my moments where I’ve blown up, but I always feel foolish afterward, like I’ve failed somehow—which doesn’t mean I won’t turn around and do it again next week. But this job is so hard. To work this hard and not be actively endeavoring to cure cancer feels like, What the hell’s the point? Most days, it’s just easier to be nice to people, and it bears more fruit, even if I’m not feeling like it.

Why do you think TV’s been so good over the past decade and a half?

The difference now is that writers are allowed to get away with more. We’re allowed to go darker. Thank God we don’t have what they had in the fifties, which was a sponsor reading all the scripts and saying, “I don’t think this character should be black.” But we could very easily have that situation again, because TV commercials get skipped over on TiVo. Ad agencies could once again take over sponsorship of individual series, and suddenly writers will be answering to them all over again.

But the best thing about cable TV is not the ability to say the F-word or show boobs or extreme violence. It’s the idea that a series lasts for thirteen episodes a season rather than 24. It’s amazing the quality of good work that happened in the fifties when a series would have to turn out 30-some episodes a season—it’s amazing that I Love Lucy was as good as it was! Or The Honeymooners. On Breaking Bad, I get to sit and spend three or four weeks an episode, breaking an episode and taking it apart, before a single word is written. That preproduction time is everything, and cable TV allows for that in a way that network TV can’t.

You seem enormously grateful to AMC and Sony for their support. Have you ever fallen out over anything?

We fight over money—or rather, I apologize for the overages that I incur and they yell at me. But I can point to a good standoff that I lost. We had an executive at AMC, a woman named Christina Wayne, who said I used too much music in my first cut of the pilot episode—I had just brought my iPod into the editing room. This executive said, “Don’t you trust your material? Do you think you need music to sell it?” I got so bent out of shape that I wrote an e-mail to her boss, which I really regret, trying to get her in trouble with him. But in hindsight, she was in the right, and if you watch Breaking Bad now, there’s more silence than music. Show writers can be wrong just as often as anybody else, and if enough people tell you that you’re drunk—or if one really, really smart person tells you you’re drunk—you need to sit down.

One of the criticisms of Breaking Bad that keeps coming up is over the female characters. Skyler White is seen by some as this henpecking woman who stands in the way of all of Walt’s fun.

Man, I don’t see it that way at all. We’ve been at events and had all our actors up onstage, and people ask Anna Gunn, “Why is your character such a bitch?” And with the risk of painting with too broad a brush, I think the people who have these issues with the wives being too bitchy on Breaking Bad are misogynists, plain and simple. I like Skyler a little less now that she’s succumbed to Walt’s machinations, but in the early days she was the voice of morality on the show. She was the one telling him, “You can’t cook crystal meth.” She’s got a tough job being married to this asshole. And this, by the way, is why I should avoid the Internet at all costs. People are griping about Skyler White being too much of a killjoy to her meth-cooking, murdering husband? She’s telling him not to be a murderer and a guy who cooks drugs for kids. How could you have a problem with that?

We’re talking now just a few days after the Boston Marathon bombings, and I’m sure you’ve been watching the news. Did you see that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev had tweeted that he was a Breaking Bad fan?

No. Jesus.

He also tweeted, “Breaking Bad taught me how to dispose of a corpse.”

Oh, for fuck’s sake. Oh, Jesus Christ. No, I did not know that.

Yours is a dark show on which fictional people do terrible things—how much do you worry about inspiring real-life lunatics?

Maybe I don’t worry as much as I should. Jesus. I co-wrote the pilot episode of The Lone Gunmen, which was a spinoff of The X-Files; in it, there was a plot to fly 767s into the World Trade Center. That was about six months before 9/11. I remember when that day came, watching CNN just like everyone else in America, just absolutely horrified, stunned into disbelief. I turned on the TV, and I’m looking at the smoke, and I’m like, Wait a minute. We wrote this. I have no evidence that any of those assholes that did that on 9/11 had ever seen the show. Not that many people had actually seen the show. But you have those moments. Hopefully, it doesn’t need to be said that you don’t want to inspire evil and madness and hatred in any way, shape, or form. It’s not going to stop me from writing. It’s not going to paralyze me. But those moments give you pause.

Have you ever worried that one of Breaking Bad’s violent moments might have gone too far?

The scene I had trouble watching in the editing room—I would actually avert my own eyes—was when Victor gets his throat slit with a box cutter. I found that agonizing to watch. Again, hopefully it goes without saying that moments like that are meant to do the opposite of make violence look attractive or sexy. They are meant to unsettle and upset. People could argue, and I would not argue back, that Breaking Bad is oftentimes too violent. But the only thing that would really trouble me is if anyone said Breaking Bad sells violence in an attractive fashion, like something for young men to strive for. That would hurt, but I don’t think we do that.

Do you think there’s ever a moral imperative to pull back on the violence?

I don’t think there should be any kind of edict or mandate imposed by anyone else. However, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to expect a writer in my position to know where to draw the line him- or

herself. It’s up to the writer to know the difference between a dark story that is basically instructive and a cautionary tale.

Breaking Bad does seems to be responsible, or at least realistic, in the way it uses guns. On the show, guns are jamming all the time, and characters get killed by their own weapons. When Walt buys a gun, the dealer lectures him on how ineffective it’ll be in a high-pressure situation.

I’m a gun owner, and I grew up in the South. Guns are ingenious mechanisms, the product of many thousands of hours of brilliant engineering. You can ascribe to them evil or good. I’ve never hunted, but I find target shooting very relaxing. But it goes without saying guns shouldn’t be used to murder innocent schoolkids. I’m not anti-gun. I’m not anti–claw hammer either. But I am against having them in the hands of lunatics.

Children are always under threat on Breaking Bad, which makes me wonder: Did you rethink anything that happens in these final episodes after the Newtown school shooting?

No. But Newtown was so fucking horrible. It’s been such a bad few months. You’re watching the news, and you see the Kardashians, and you’re like, Is this the best news people can give us? And then you have a week like this one [with the Boston Marathon bombings and the subsequent manhunt], and you’re like, Bring back the Kardashians!

How do you identify yourself politically?

I’m not real comfortable talking about politics. I’m probably more conservative than most folks in the business. But the best way I can put it to you is, here at age 46, I am less interested in politics than I’ve ever been in my life. Politics don’t serve a lot of good. I’m not talking about government—government serves a lot of good. But politics don’t seem to be reaping a lot of positive benefits these days.

What do you think of the drug laws in the U.S.?

I understand why a drug like meth would be illegal, but I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about our laws. Our country is run by good people, more or less, who want the best for their own families, but as with most things that pass through the filter of politics, things get messed up. The idea of keeping illegal drugs out of the hands of little kids is a sound idea. But I don’t pretend to have any answers about how things could suddenly, instantly, magically be better overnight.

How did you settle on meth as the central drug in the show? It’s obviously not the sexiest drug.

I was on a phone call in 2004 with Tom Schnauz, who was a writer with me on The X-Files. We’ve known each other since NYU back in the eighties. He had read a New York Times article about a meth lab somewhere that was getting a bunch of neighborhood kids sick. We were trying to figure out what we were going to do next, because The X-Files had just ended and writing jobs were few and far between. “Should we be greeters at Walmart? Should we put a meth lab in the back of an RV?” It was in the midst of joking around that this idea struck home: What would an otherwise law-abiding person be doing in a meth lab in the back of an RV? That was the eureka moment for me.

And meth makes perfect sense, story-wise, for Breaking Bad. Unlike marijuana or cocaine, it’s a completely synthesized drug that needs a chemist and not a farmer to make. I liked the idea of Walt being good at chemistry and having a unique set of skills that would allow him to cook the best meth available. And it’s also just a nasty, terrible drug that destroys people and whole communities.

How did you choose Albuquerque as the setting? The Southwest is the fastest-growing part of the U.S., but it’s not often portrayed in entertainment.

It was a wonderful happenstance, but it was borne strictly of economics. Albuquerque and the State of New Mexico have been very welcoming in a way that California has not. In the first script, Breaking Bad was set in Southern California, in Riverside. During preproduction, Sony said, “What do you think about shooting in Albuquerque, New Mexico? We’ll get a 25 percent rebate on monies spent within the state.” I thought, You know what? More money on the screen. How can you turn that down? They said, “It’ll be great. All you’ll do is replace the license plates and call it California.” I said, “No, then we’d be shooting in a town where we can never look east.” We’d always have to be avoiding the Sandia Mountains! So we changed the setting to New Mexico.

Is there any product placement on Breaking Bad?

Chrysler has been great to us. Walt bought Junior a Dodge Challenger. Walt does doughnuts and then he lights the thing on fire and he blows it up. I was amazed they let us do that. Talk about product misuse.

But some of the moments that seem like overt product placement were not. We gave free ad time to Funyuns. We used Denny’s a couple of times, and Denny’s never paid us a dime. I think we had to pay for the privilege. I just love the idea of Denny’s as a place Walt and Jesse would go after having watched a guy get his throat slit. They put him in a barrel and dissolve him with acid, then they say, “Hey, let’s go to Denny’s. We’ll get a Grand Slam.” Chili’s and the Olive Garden turned us down, by the way.

What’s your obsession with fast food? There’s Gus’s chicken restaurant on Breaking Bad, and there’s Home Fries, the 1998 Drew Barrymore–Luke Wilson movie that you wrote, which was set in a burger place.

I spent a lot of time in fast-food restaurants as a kid. God, I remember the first McDonald’s in the little town where I grew up, Farmville, Virginia. When I was about 10 years old, the first McDonald’s went up, and that was like the biggest treat in the world. So I don’t know, maybe it hearkens back to that. I’m not as enamored of it now. I’ve been able to eat at the French Laundry since then, so McDonald’s has kind of paled.

In this issue, our TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz argues that TV has become a director’s medium.

I disagree. There’s a perfectly good medium for directors, and it’s called film. TV is a writer’s medium. I am chauvinistic toward writing because that’s where I came from. And when executives get excited about getting a superstar movie director to direct the pilot of a new TV show, I think to myself, That’s all well and good, but what happens after that? That superstar director goes away, and you’ve still got 100 hours to fill. Who’s the first person on the ground making those 100 hours happen? It’s invariably the writer.

Have shows like yours changed the mission of movies, do you think? A two-hour movie can’t explore a character’s psychology nearly as well as a six-hour TV series. With movies like Lincoln and Zero Dark Thirty, you’re seeing more procedurals that dispense with backstory altogether, presumably because they can’t do the job as well.

I love movies, and I love TV. In TV, you have the time to get deeper into a character, but movies are a two-hour block of time in which we get transported to another place. We’ll always have Paris, and we’ll always have movies. But we’re going through a time, unfortunately, when the big movie studios are run by folks that are more obsessed than ever with the bottom line and who probably love movies less than any studio hierarchy that’s ever existed in my life. Back in the day, when the Irving Thalbergs and Louis B. Mayers ran the business, those guys could bite your head off. Those guys were tough sons of bitches, but they loved movies. They weren’t obsessed with counting beans. The problem with the movie business now is that it’s marketing-driven—driven by demographics, by spreadsheets and flowcharts and all this shit that has nothing to do with storytelling. But the movie itself, the structure of the movie, will always be with us. And occasionally a really great movie for grown-ups does sneak through.

It seems like it’s harder to get a green light for a smart movie than to actually make one.

I learned a great lesson from Michael Mann years ago. I was working on a script for him that became Hancock. It was a rewrite I was doing of someone else’s script, and I said to Michael in one of the first meetings, “What is this about? What’s the theme of it? What do we want to impart to the audience on a subconscious level?” He just looked at me kind of blankly and said, “Vince, come up with a good character, tell the story, and keep the audience engaged. Themes are for professors with patches on their elbows.” I learned not to get hung up on the subtext. Just pay attention to what’s going on under your nose, and the rest will take care of itself.

Which other TV shows do you watch?

I watch more TV than I should when I get home, because I need it to decompress. I invariably wind up watching non-scripted stuff. I don’t mean reality TV—I’m not a big fan of that, because honestly it’s as scripted as Breaking Bad is. I love documentaries. But put me in front of a TV that’s playing Modern Marvels, I’ll watch that for ten hours straight. Like the history of carbon and all its many uses, or tungsten, or how do they strip-mine a mountain, or how they make explosives. How It’s Made is a fun show. I love the Food Network. I love Good Eats. I don’t want politics. I don’t want characters. I want to learn how something is made, how it was created, who came up with it.

There’s also a channel, ME TV, that I watch endlessly—old episodes of Columbo and Perry Mason, which I didn’t know that well. I’ll watch Twilight Zone anytime it’s on the air even though I’ve seen it a hundred times. I’ll watch Lost in Space or Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea. They’ve got all these fun old fifties and sixties shows that are very well written, and yet because they’re so far in the past, they allow me to just turn my brain off and vegetate, which is something I need when I get home.

I was in a pitch meeting with the head of a network, and I started to pitch Breaking Bad, and he says, “It sounds a little like Weeds.” I said, “What is Weeds?” I’m pretty sure it hadn’t gone on Showtime yet, and regardless I didn’t have Showtime. If I’d known about Weeds, I would have never pitched Breaking Bad.

With Breaking Bad nearly over, what will you do next? How serious is the talk about a Saul Goodman spinoff series?

We’re in early discussions for a spinoff. In my dream version of it, I would help create the pilot and arc out the first season and then basically transition away and let Peter Gould, who created the character, run it.

What would the tone be?

We’re still trying to figure out whether it’s a half-hour or an hour. It’s lighter than Breaking Bad, but it’s not a sitcom. I have a hard time with most modern sitcoms because the structure is so self-limiting. You have to have a laugh every eleven seconds, which is so artificial. It’s like Kabuki theater. It’s so unrealistic to me. Not to cast aspersions toward an entire art form, I just have a hard time relating to sitcoms, except for older ones like All in the Family, which were leavened with plenty of drama.

I rewatched all 54 hours of Breaking Bad last week to prepare for this interview, and I found myself enjoying it more than I did when I was watching week to week. How do you think binge-watching changes the experience of your show?

I don’t know, because I’ve never binge-watched anything. My butt starts hurting too much. But I’ll tell you, I am grateful as hell for binge-watching. I am grateful that AMC and Sony took a gamble on us in the first place to put us on the air. But I’m just as grateful for an entirely different company that I have no stake in whatsoever: Netflix. I don’t think you’d be sitting here interviewing me if it weren’t for Netflix. In its third season, Breaking Bad got this amazing nitrous-oxide boost of energy and general public awareness because of Netflix. Before binge-watching, someone who identified him- or herself as a fan of a show probably only saw 25 percent of the episodes. X-Files fans would say to me, “I love that show. I’m a big fan.” I’d say, “Well, did you see this episode?” “No. I didn’t see that one. Which ones did you write?” And every episode they’d mention would be one I didn’t write. But it’s a different world now.

Having binge-watched, I have to ask: What can you tell me about the ending of Breaking Bad?

In my mind, the ending is a victory for Walt. You might see the episode and say, “What the fuck was he talking about?” But it’s a somewhat happy ending, in my estimation.

*This article originally appeared in the May 20, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.