Story and visual influences on The X-Files : Season 5

– Season 5 [1997-1998] –

5X02: Redux

– The Parallax View (Alan J. Pakula, 1974)

Another classic 1970s conspiracy thriller from the same director as “All the President’s Men” (see 1X23: The Erlenmeyer Flask, 5X20: The End) in a wave of films (see also 3X01: The Blessing Way for “Three Days of the Condor”) that came in the aftermath of the assassination of John F. Kennedy (1963) and the Watergate scandal (1972-1974), events that also influenced Chris Carter. Inspired by the investigation into JFK’s assassination and Lee Harvey Oswald’s assassination just two days after JFK’s, this film deals with the investigation of a reporter that brings him to the discovery of a company, the Parallax Corporation, that deals with recruiting political assassins; the assassinations are then blown away by special committees and the press as the acts of isolated lone gunmen, preventing any conspiracy theories from anchoring themselves in the public dialogue — introducing the anti-conspirationist “lone gunman” theory in popular culture. This seminal conspiracy film and its feeling of paranoia must have inspired the X-Files mythology in general, as well as the anti-government paranoia of the Lone Gunmen. The Parallax Corporation can be seen as a model for the X-Files’ all-present, faceless, sprawling governmental conspiracy described by Kritschgau here, and for the Syndicate itself.

– JFK (Oliver Stone, 1991)

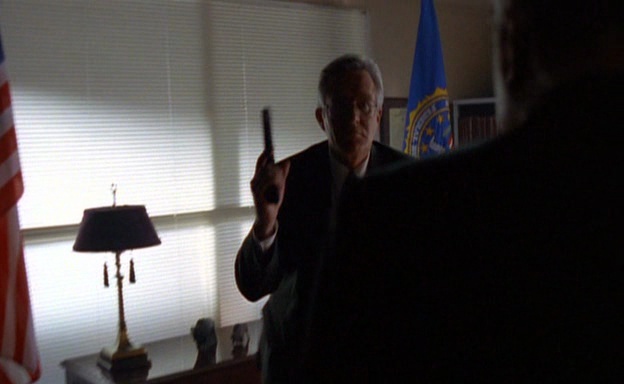

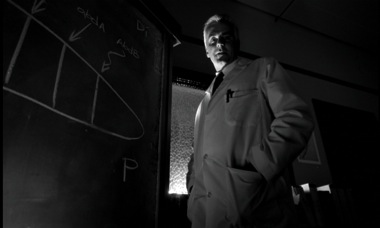

When Kritschgau explains 50 years of world history to Mulder while walking through corridors with an avalanche of dialogue, Kritschgau and Mulder are inter-cut with a frantic montage of real historical footage that illustrate Kritschgau’s words: images of post-World War II negotiations, Khrushchev, the Korean War, medical experiments on civilians, Eisenhower, the Gulf War, … The exact same technique is used in “JFK”, where the aptly named “X” (Donald Sutherland) explains to the protagonist (Kevin Costner) the ins and outs of the military-industrial complex and how it resulted in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. The similarities are all the more notable since both revelatory discussions deal with the same issue: the military-industrial complex and the conspiracies that result from it.

|

|

5X03: Redux II

– The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972)

Frank Spotnitz has acknowledged that the final scenes of “The Godfather” served as an inspiration for the climactic scenes of this episode. A series of events set in motion by the protagonist Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) throughout the film result in a number of assassinations that are shown in a rapid montage, while Michael is attending the baptism of his son in church. Redux II follows the same intense buildup and montage: while Mulder testifies in front of the FBI board and makes an accusation, we are quickly shown Scully suffering in the hospital, the CSM being shot, and Scott Blevins being shot.

|

|

|

|

– Star Wars Episode VI: The Return of the Jedi (Richard Marquand, 1983)

There are several scenes in literature and film where the devil tempts the hero, and one of the most memorable in modern pop culture is the Emperor (Ian McDiarmid) tempting Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) to join him in the Dark Side in the final showdown of “Star Wars”. The similarities with the CSM’s temptation of Mulder to work with the dark Syndicate can be found in the fact that also present against Luke is his father Darth Vader; the ambiguity on whether the CSM is Mulder’s real father is an underlying thread since season 3.

5X04: Detour

– Predator (John McTiernan, 1987)

The nearly invisible beings and the woodland setting in this episode are similar to the creature that uses an invisibility cloak in a jungle setting in the movie.

|

|

|

|

5X06: Post-Modern Prometheus

– Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (Mary Shelley, 1818)

The entire story is of course another take on the Frankenstein myth, born from the legendary 1818 novel by Mary Shelley and adapted countless times in cinema. The episode title is an evolution of the novel’s subtitle, both chronologically in a sense (“post-”) and in the nature of the episode: in the way the story recycles and parodies the original, in the way pop culture references are added in (comic books, TV talk shows), in the overall tone, this episode is indeed a fine example of the post-modern artistic movement.

Another reference: Dr. Polidori’s wife is named Elizabeth — same as Dr. Frankenstein’s wife-to-be in the book.

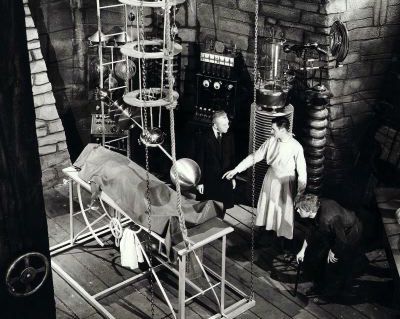

– Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931)

More explicitly, this episode recreates and parodies the 1931 movie adaptation: black-and-white image, gothic imagery and at times fake-looking sets, the matte paintings for the sky in pastel shades of grey, the imagery of the angry mob carrying torches seeing the death of the monster in an old mill (an old barn in the episode). The 1931 is the most famous and influential adaptation, memorably featuring Boris Karloff as the monster.

|

|

|

|

|

|

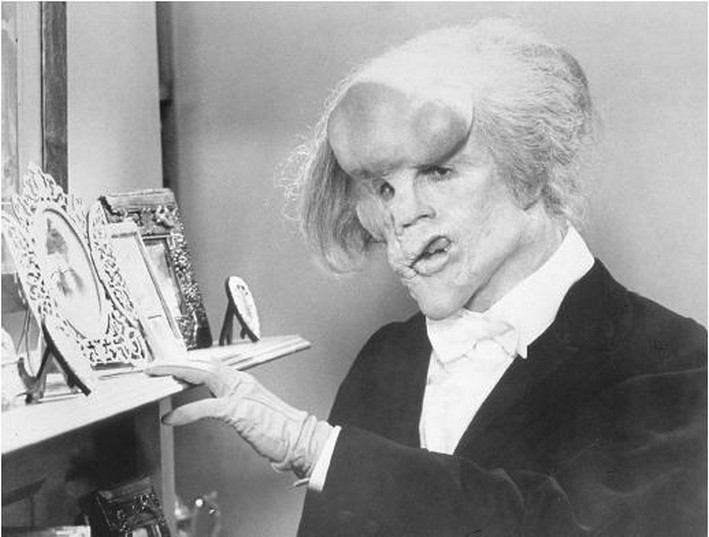

– The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980)

The episode mixes in elements from another black-and-white monster movie: Lynch’s film depicts a horribly disfigured man (John Hurt) who is exhibited as a freak in a circus, based on the true story of Joseph Merrick. By letting the audience in in the emotional life of the man, we progressively move beyond our initial disgust or freak fascination towards truly caring for the hurt soul that is behind this disfigured body. The episode does exactly the same with its Great Mutato (Chris Owens).

|

|

5X09: Schizogeny

– The Evil Dead (Sam Raimi, 1981)

The seminal thriller features a famous “tree rape” scene, where one of the girls gets lost in the woods and is literally raped by trees possessed by demons. This is similar to the episode, where much of the case involves moving plants.

|

|

– Poltergeist (Tobe Hooper, 1982)

Another possible inspiration, at one scene in this iconic thriller, a tree becomes “alive” and abducts a little boy through the window of his house. A very similar scene occurs in the episode, where the father is pulled from a window probably by something vegetal.

|

|

|

|

5X10: Chinga

The “demonic toys” trope is an old one in horror films, with many examples going back decades (for example, “Devil Dolls”, 1964). But more recently there are a few that could have shaped the ideas of writers Stephen King and Chris Carter for this episode.

– Dolls (Stuart Gordon, 1987)

A family is attacked by dolls when they have to spend the night in a countryside house; the dolls prove to be imprisoned souls that were put there as punishment by the owners of the house. The similarities with the episode are that the main character of the film is also a little girl, who manages to come to good terms with the dolls because of her pureness in spirit.

|

|

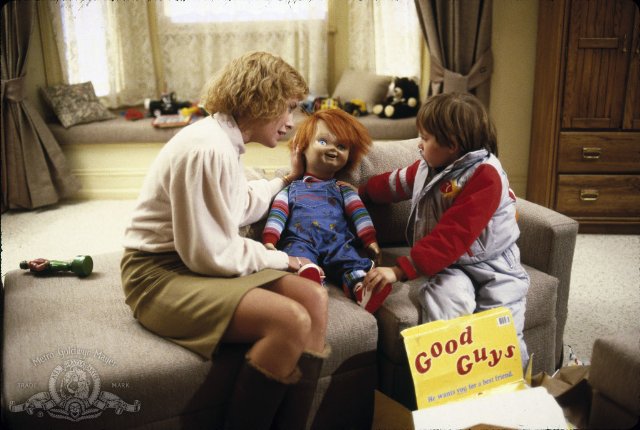

– Child’s Play (Tom Holland, 1988)

This is the first of the “Chucky” franchise, which spawned 4 sequels and counting. Chucky is a serial killer (Brad Dourif, memorable for portraying Luther Lee Boggs in 1X12: Beyond the Sea) who transfers his soul into a doll to escape pursuit from the police; he then betrays his successive owners and keeps on killing.

|

|

– It (Tommy Lee Wallace, 1990)

Towards the beginning of the episode, the doll “awakens” while the mother is hanging the laundry in her garden and talking on the phone. We see the menacing shadow of the doll behind the hanging sheets, blown by the wind. This scene is very similar to an apparition of the titular “It” in the mini-series adaptation of the novel: the clown appears half-hidden behind sheets hung to dry, suddenly he’s not funny anymore, and murder ensues off-camera. The similarities are the more striking since “It” is one of Stephen King’s most iconic novels.

|

|

|

|

– Jumanji (Joe Johnston, 1995)

This great family adventure is about a magic board game that goes from owner to owner, in the same way the doll in the episode “uses” its owners before passing on to the next ones. The epilogues of film and episode are notably similar: in a setting entirely disconnected from the rest of the story, the board/doll is discovered again, announcing more mayhem to come. The tone of the works is entirely different and this similarity can be found in many other works (episodes like 1X04: The Jersey Devil or 3X22: Quagmire end the same way too), so this is hardly an inspiration at all.

5X11: Kill Switch

– Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982)

The makeup and general costume design donned by the hacker in this episode is reminiscent of that of the artificial human Pris (Daryl Hannah) in Ridley Scott’s masterpiece, notably in the eyeliner. “Blade Runner” and its unique aesthetic was a forerunner in the definition of the cyberpunk sub-genre of science fiction in the early 1980s as different elements started coming together at that time; one of the key elements was the publication of the novel “Neuromancer” in 1984 by William Gibson, who also wrote the script for this episode. In all these works we can see a common gothic and cyberpunk aesthetic.

|

|

5X12: Bad Blood

– Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950)

The entire episode is an X-Files take on the famous Kurosawa masterpiece film, by writer Vince Gilligan’s acknowledgment. Both works play with the concept of subjective interpretations of reality: depending who you ask what happened, you get quite different stories. This is used to great comical effect in the episode, given the typical behavior of Mulder and Scully that has been now established over more than 100 episodes, whereas the tone of the film is much more serious. In the film, a murder has occurred and a court is summoned to hear out testimonies and establish the guilty; four different versions are heard by the court and reconstituted in the movie, all mutually contradictory. This is the same as in the episode, where the murder of the pizza boy has occurred and Mulder and Scully tell their versions of what happened to each other. In the film, the last version of the story is the one that seems to be the most objective, however it does not seem to contain the entirety of the truth either, making “the truth” an unaccessible ideal — a very X-Filish idea. The concept has been used in film and television extensively (the “Rashomon effect”), including by the X-Files before, in 3X20: José Chung’s ‘From Outer Space’.

5X13: Patient X

– I, Claudius (Herbert Wise, 1976)

Frank Spotnitz has mentioned that in writing the mythology episodes, works like the BBC mini-series “I, Claudius” were an influence, in particular in the way main characters interacted and plots rolled out. “I, Claudius” is a 12-episode adaptation of the 1934 novel by Robert Graves and narrates the first 80 years of the Roman Empire as seen by its ruling members that essentially all belong to the same family, along with the conspiracy plots, the temporary alliances and the back-stabbing (or poisoning) betrayals that go with each succession in the throne. The theatrical approach and care of the dialogues along with fine acting made this series a success, and became an inspiration on how mythology writers Spotnitz and Carter wrote the interactions between the Syndicate members, the Spender family members and Mulder and Scully.

5X15: Travelers

– The Puppet Masters (Robert A. Heinlein, 1951)

Five years before the film “The Invasion of Body Snatchers” came out this novel from science fiction legend Heinlein was already mixing the Cold War with an alien invasion, describing a future where slug-like aliens take over the human hosts by being attached to their necks, and the war of paranoia and armed resistance that follows.

– The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel, 1956)

This classic sci-fi thriller describes an alien invasion where people in a an American town are progressively being replaced by aliens, who use their bodies as disguise. Although it was not the intention of the film-makers (or so it seems), this film was perceived from early on as an allegory on the USA’s fear of Communism and as commentary on the general paranoia of the Cold War. This episode harkens back to this film and era, the 1950s, a time when patriots feared their very neighbor could be an infiltrated communist “fellow traveler”, and when FBI founder/director J.E. Hoover and Senator McCarthy doing everything in their jurisdiction — and then some — to prevent that.

– The Hidden (Jack Sholder, 1987)

The film deals with a police officer (Michael Nouri) and an FBI agent (Kyle MacLachlan) who discover that what is responsible for a series of murders is an alien being that takes control of human bodies. Apart from the X-Files-like story (see 1X07: Ice, 3X15: Piper Maru), the look of the alien creature and the way it jumps from host to host is strikingly similar to the being in this episode: an arachnoid creature emerging from the mouth of the host.

|

|

5X16: Mind’s Eye

– Eyes of Laura Mars (Irvin Kershner, 1978)

Laura Mars (Faye Dunaway) is a photographer who develops a sense of seeing through the eyes of a killer, in real time, and uses that as an inspiration for producing her own art photos. The paranormal phenomenon is the same as in the episode, although in the episode there is the added effect of the person in question (Lili Taylor) being blind.

|

|

5X18: The Pine Bluff Variant

– The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (John Le Carré, 1963)

The episode is directly inspired by this novel, or the Martin Ritt-directed film that came out two years later. John Le Carré is famous for writing a large number of novels taking place in the world of espionage, and this novel was particularly influential in the way it presented both “sides” engaging in actions beyond an moral considerations in order to reach their objective.

The premise of the book involves a British spy sent to East Germany during the Cold War; he manages to infiltrate Communist circles and arrives in the middle of an internal power struggle in East Germany; eventually the reveal that he was indeed a spy triggers a series of events that shows that this reveal was part of the plan of the British intelligence all along; he is released by another undrecover spy.

The episode closely follows these plot points, including the last twist in which Mulder is about to be executed by Bremer but is then released by him, proving he was working undercover for the CIA all along. (The episode doesn’t follow the tragic ending of the book though!)

5X20: The End

– All the President’s Men (Alan J. Pakula, 1976)

Along with the scenes with Deep Throat (see 1X23: The Erlenmeyer Flask), the most obvious scene that harkens back to the meetings in dark alleys or staircases between the real Deep Throat and Woodward (Robert Redford) is in this episode, in the meeting between the CSM (William B. Davis) and Jeffrey Spender (Chris Owens) in a dark underground parking lot.

|

|

|

|

Leave a Reply