March / April 2004

Development of Beliefs in Paranormal and Supernatural Phenomena

Skeptical Inquirer Volume 28.2

Christopher H. Whittle

[Original article here]

A new study found high levels of fictional paranormal beliefs derived from broadcasts of The X-Files in viewers who had never watched The X-Files. An examination of the origins of paranormal and supernatural beliefs leads to the creation of two models for their development. We are taught such beliefs virtually from infancy. Some are secular, some religious, and some cross over between the two. This synergy of cultural indoctrination has implications for science and skeptics.

Two important findings emerged from a recent study I conducted on learning scientific information from prime-time television programming (Whittle 2003). The study used an Internet-based survey questionnaire posted to Internet chat groups for three popular television programs, The X-Files, ER, and Friends. Scientific (and pseudoscientific) dialogue from ER and The X-Files collected in a nine-month-long content analysis created two scales, ER science content and The X-Files pseudoscience content. Respondents were asked to agree or disagree with statements from each program (such as, “Rene Laennec used a rolled-up newspaper as the first stethoscope” [ER], and “The Wanshang Dhole, an Asian dog thought to be extinct, has pre-evolutionary features including a fifth toe pad, a dew claw, and a prehensile thumb” [The X-Files].

My first finding, that ER viewers learned specific ER science content, is an indicator that entertainment television viewers can learn facts and concepts from their favorite television programs. The second finding was spooky. There was no significant difference in the level of pseudoscientific or paranormal belief between viewers of ER and The X-Files. This finding does not seem surprising in light of Gallup and Harris polls demonstrating high levels of paranormal belief in the United States, but the beliefs assessed in the study were fictional paranormal and pseudoscientific beliefs created by the writers of The X-Files. Paranormal researchers ask questions such as, “Do you believe in astral projection, or the leaving of the body by one’s spirit?” My research asked, [Do you believe] “[d]uring astral projection, or the leaving of the body for short periods of time, a person could commit a murder?” A homicidal astral projector was the plot of an X-Files episode, but ER viewers were just as likely to acknowledge belief in that paraparanormal (a concept beyond the traditional paranormal) belief as were viewers of The X-Files!

Perhaps it is as Anderson (1998) pointed out in his Skeptical Inquirer article “Why Would People Not Believe Weird Things,” that “almost everything [science] tells us we do not want to hear.” We are born of primordial slime, not at the hands of a benevolent and concerned supreme being who lovingly crafted us from clay; we are the result of random mutations and genetic accidents.

Anderson cited quantum mechanics as a realm of science so fantastic as to have supernatural connotations to the average individual. Quantum physicists distinguish virtual particles from real particles, blame the collapse of the wave function on their inability to tell us where the matter of our universe is at any time, and tell us that in parallel universes we may have actually dated the most popular cheerleader or football quarterback in high school, whereas in this mundane universe, we did not. It is all relative. Ghosts are a fairly predictable phenomenon compared to the we-calculated-it-but-you-cannot-sense-it world of quantum physics. Most people will agree that ghosts are the souls of the departed, but quantum physicists cannot agree on where antimatter goes. It is there but it is not. Pseudoscientific and paranormal beliefs provide a sense of order and comfort to those who hold them, giving us control over the unknown. It is not surprising that such beliefs continue to flourish in a world as utterly fantastic as ours.

After researching the paranormal in an effort to discover why ER viewers might have the extraordinary paranormal beliefs indicated on their survey questionnaires, I constructed two models of paranormal belief from my research notes (heavily drawn from Goode 2000, Johnston et al. 1995, Irwin 1993, Vikan and Stein 1993, and Tobacyk and Milford 1983). Figure 1 shows the interrelationship between the natural environment, human culture, and the individual. The culture and the individual maintain General Paranormal Beliefs, which consist of at least four relatively independent dimensions: Traditional Religious Belief, Paranormal Belief (psi), Parabiological Beings, and Folk Paranormal Beliefs (superstitions). Individuals have cognitive, affective, and behavioral schema in which these beliefs are organized. Society creates and maintains paranormal beliefs through cultural knowledge, cultural artifacts (including rituals), and expected cultural behaviors. The “Need for control, order, and meaning” domain is speculative on the culture side, but supported by research on the individual side. The demographic correlates of traditional religious paranormal belief and nonreligious paranormal belief (see Rice 2003, Goode 2000, Irwin 1995, and Maller and Lundeen 1933) are highly variable and generally reveal low levels of association. It seems that almost everyone has some level of paranormal belief but scientists find few reliable predictors of these levels. [See “What Does Education Really Do?” by Susan Carol Losh, et al., Skeptical Inquirer, September/October 2003.]

A first step in future work is to identify the nonbelievers in paranormal phenomena and then explore why they are nonbelievers. Belief in the paranormal begins almost from infancy. We need to expand the research on the developmental stages of belief in the paranormal, and to do that we must study young children.

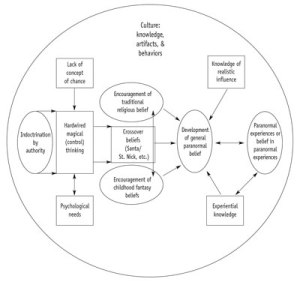

I have developed a linear model for the development of paranormal and supernatural beliefs at the individual level (figure 2). As children we are taught by parents and other adults (indoctrination by authority) about our culture’s beliefs and practices. Our elders’ teachings are filtered through hard-wired psychological processes. These include: control (magical) thinking, which allows a helpless infant to believe that he controls the actions of those around him (“Mother fed me because I pointed at her and smiled”), reducing his frustration level; psychological needs and desires, including making order and sense out of one’s environment, having an understanding of one’s place in the cosmos, feeling in control of one’s destiny, and having a fantasy outlet; and the desire to please and imitate adults.

Figure 2: Cultural and biological origins model of paranormal beliefs and experiences in the individual.

We are taught about angels, witches, devils, spirits, monsters, gods, etc. virtually in the cradle. Some of these paranormal beliefs are secular, some are religious, and the most pernicious are crossover beliefs, beliefs that are at times secular and at other times religious. Santa Claus, angels and vampires, ghosts and souls, and the Easter Bunny are examples of cross-over beliefs. Crossover beliefs are attractive to children (free candy and presents), and on that basis they are readily accepted. The devils, ghosts, and monsters are reinforced through Halloween rituals and the mass media. As the child matures, some crossover beliefs, called “teaser” paranormal beliefs, are exposed as false. Traditional religious concepts are reinforced as “true and real.” They give us Santa Claus and we believe in an omniscient, beneficent old elf and then they replace Santa with God, who is typically not as generous as Santa Claus and whose disapproval has more serious consequences than a lump of coal. We learn about God and Santa Claus simultaneously; only later are we told that Santa Claus is just a fairy tale and God is real.

In a synergy of cultural indoctrination and the individual’s cognitive and affective development, a general belief in the paranormal and the supernatural forms. Once we have knowledge of the paranormal, we can then experience it. One cannot have Bigfoot’s baby until one is aware that there is a Bigfoot, or aliens, or ghosts. In other words, you cannot see a ghost until someone has taught you about ghosts. Countervailing influences, experiential knowledge, and knowledge of realistic influence have little effect on paranormal beliefs because they are applied after the belief is established through cultural and familial authority.

The dismal statistics presented on the science literacy level of scientists and science educators by Showers (1993) argued against a rapid increase in science literacy. Scientists and science educators (1) have high levels of paranormal and pseudoscientific belief, (2) do not use their scientific knowledge when voting, (3) use nonscientific approaches in personal and social decision-making, and (4) do not have high levels of science content knowledge outside of their specific disciplines. How can we expect nonscientists to think and act scientifically if scientists and science educators do not? If we decide to mount a concerted program to disabuse the public of paranormal and pseudoscientific beliefs, we must first ask if cultures can survive without paranormal beliefs.

The media may provide fodder for pseudoscientific beliefs and create new monsters and demons for us to believe in, but each individual’s culture is responsible for laying the groundwork for pseudoscientific and paranormal belief to take root. We can inform the public through dialogue in entertainment television programming about important scientific facts and concepts. We can inform the public in formal and informal science education environments, but we probably cannot greatly reduce paranormal belief without somehow fulfilling the needs currently fulfilled by it. Science educators must focus on what changes we can make and how to best make those changes. We must involve all stakeholders in the discussion of what is an appropriate level of science literacy. To paraphrase Stephen Hawking, then we shall all, science educators, scientists, and just ordinary people, be able to take part in the discussion of why it is that pseudoscientific beliefs exist. If we find the answer to that, it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason – for then we should know the mind of God.

References

- Anderson, Wayne R. 1998. Why would people not believe weird things? Skeptical Inquirer 22(5): 42-45, 62.

- Goode, Erich. 2000. Paranormal Beliefs: A Sociological Introduction. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press.

- Irwin, Harvey J. 1993. Belief in the paranormal: A review of the empirical literature. The Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 87(1): 1-39.

- Johnston, Joseph C., Hans P. De Groot, and Nicholas P. Spanos. 1995. The structure of paranormal belief: A factor-analytic investigation. Imagination, Cognition, & Personality 14(2): 165-174.

- Maller, J., and G. Lundeen. 1933. Sources of superstitious beliefs. Journal of Educational Research 26(5): 321-343.

- Rice, Tom W. 2003. Believe it or not: Religious and other paranormal beliefs in the United States. Journal for Scientific Study of Religion 42(1): 95-106.

- Showers, Dennis. 1993. An Examination of the Science Literacy of Scientists and Science Educators. ERIC Document ED 362 393. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching. Atlanta, Georgia.

- Tobacyk, Jerome J., and Gary Milford. 1983. Belief in paranormal phenomena: Assessment instrument development and implications for personality functioning. The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44(5): 1029-1037.

- Vikan, Arne, and Erik Sten. 1993. Freud, Piaget, or neither? Beliefs in controlling others by wishful thinking and magical behavior in young children. Journal of Genetic Psychology 154(3): 297-315.

- Whittle, Christopher H. 2003. On learning science and pseudoscience from prime-time television programming. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico.

Christopher H. Whittle

Christopher H. Whittle holds a B.S. degree in Earth Sciences from the University of Massachusetts, an Ed.M. from Harvard University, and a Ph.D. from the University of New Mexico.